HERITAGE AND ORIGINS

The founding of the Society is rooted in the personal historical background and cultural lineage of its founder. This connection is not presented as a matter of private family inheritance, but rather as an entry point for understanding the broader civilizational development of Manchuria and Northeast Asia, opening into a wider narrative of multi-ethnic cultural history. The Society thus approaches this history not through dynastic narration, but through the broader lens of regional civilization and cultural interaction.

From a historical and international scholarly perspective, “Manchuria” is not the product of a single people or a single regime, but a Northeast Asian civilizational sphere shaped through long-term interaction, contact, and integration among numerous ethnic groups. The Tungusic Jurchen–Manchu peoples, as one of the principal sources, lived alongside and interacted continuously with Mongols, Hezhen, Oroqen, Evenki, Daur, Xibe, Koreans, Han communities, and other Northeast Asian populations. Together, these groups formed the historical foundation of Manchuria as a profoundly multi-ethnic cultural landscape.

Within this extended process of interethnic interaction, the Manchu language and culture gradually developed their distinctive civilizational character. The evolution of the Eight Banner system integrated military organization, administration, social structure, and daily life into a unified framework. Dress, ritual, belief systems, language, and modes of living became deeply interconnected within this institutional structure, giving rise to a composite cultural identity that transcended any single ethnic origin. This civilizational form cannot be reduced to one people alone, but reflects the cumulative outcome of long-term, multi-ethnic co-existence and cultural exchange.

From the standpoint of public culture and academic research, the Society re-examines this history not as the memory of a single lineage or a single historical group, but as a shared cultural heritage belonging to society and to the wider world. By situating regional histories within the broader civilizational continuum of Manchuria and Northeast Asia, the Society seeks to explore how political institutions, language systems, and everyday cultural practices together shaped a living civilization that continues to influence contemporary cultural identity, historical memory, and cross-cultural expression.

FOUNDER & CULTURAL LEGACY IN PRACTICE

The founder, Cecilia Aisin-Gioro(恒钦), traces her family background to the last imperial lineage in Chinese history, the Aisin-Gioro clan. This historical connection is not presented as a personal or political claim, but rather as part of a broader cultural and historical context that informs her engagement with heritage, art, and public culture.

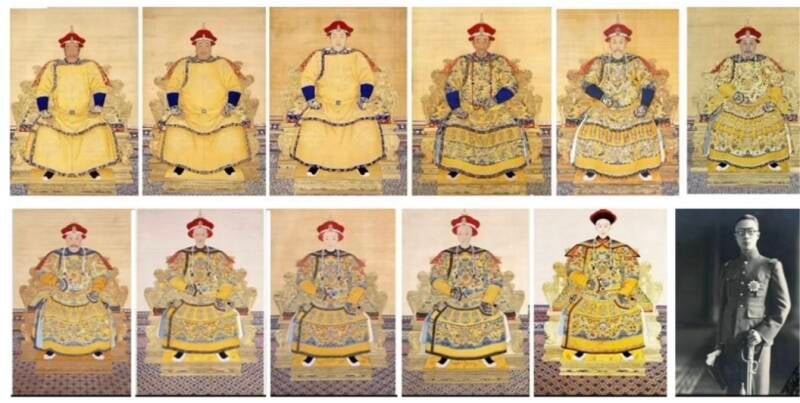

The Aisin-Gioro lineage originated within the Tungusic Jurchen world of Northeast Asia. In 1616, its ancestor Nurhaci unified the Jurchen tribes and established the Later Jin state. In 1636, his son Hong Taiji renamed the state the Great Qing and formally established “Manchu” as both a national and ethnic designation. In 1644, Qing forces entered the Central Plains, replaced the Ming dynasty, and subsequently ruled China for nearly three centuries. This historical process represented not merely a dynastic transition, but the formation of a vast multi-ethnic political and civilizational system centered on Manchuria.

Under Qing rule, the empire expanded to an unprecedented territorial scale, incorporating Xinjiang, Tibet, Mongolia, and Taiwan into a unified imperial framework. This political consolidation significantly shaped the foundations of China’s modern borders, while also bringing together a wide range of peoples, belief systems, and cultural traditions within a shared historical structure.

Beyond political history, the Aisin-Gioro lineage also nurtured a long tradition of art, literature, and scholarship. Across generations, members of the family contributed to painting, calligraphy, poetry, and cultural research. The family produced numerous artists and intellectuals who became influential figures in modern Chinese cultural life. Notable examples include Pu Ru (溥儒,),also known as Pu Xinyu), celebrated as one of the “Four Masters of Modern Chinese Painting”; Pu Quan (溥佺)recognized for his achievements in calligraphy and classical studies; Yu Zhan (毓嶦)a distinguished calligrapher; and Qi Gong (启功), a renowned calligrapher, scholar, and educator who played a major role in twentieth-century Chinese cultural and academic life.

Today, the significance of this legacy is understood not in terms of political authority, but as a form of cultural inheritance. For contemporary descendants and cultural practitioners, this history serves as an intellectual and ethical foundation for engagement with public culture, education, dialogue, and the shared value of heritage across nations and communities.

MANCHURIA

From an international historical and scholarly perspective, “Manchuria” refers not merely to a modern administrative region, but to a long-standing civilizational space within Northeast Asia. It represents a broad historical and cultural landscape formed through centuries of ecological adaptation, interethnic interaction, migration, and political transformation.

Historically, Manchuria extended beyond the boundaries of what is today known as Northeast China, encompassing vast areas across the Amur (Heilongjiang) River basin, the Ussuri River region, and wider Northeast Asian borderlands. In modern international scholarship, parts of this historical region are referred to as “Outer Manchuria,” now largely within the territory of the Russian Far East. Together with what is often called “Inner Manchuria” today, these areas formed a continuous cultural and geographic zone shaped by shared environmental conditions and long-term human activity.

Manchuria has long been recognized as a key homeland of Tungusic-speaking peoples, particularly the Jurchen–Manchu groups, and as a crossroads of multiple ethnic communities. Over many centuries, Jerchen, Hezhe, Oroqen, Evenki, Daur, Xibe, Korean, Mongol, Han, and other Northeast Asian peoples lived, migrated, traded, intermarried, and interacted across this region. Through these sustained encounters, Manchuria developed into a profoundly multi-ethnic and culturally layered civilizational space.

The cultural landscape of Manchuria was shaped by its distinctive ecology of forest, river, steppe, and cold-climate environments. Hunting, fishing, pastoralism, agriculture, and frontier trade formed interconnected ways of life. Shamanistic belief systems, clan-based social organization, and multilingual communication traditions emerged alongside later state institutions. Together, these elements produced cultural systems that cannot be reduced to any single ethnic origin or political regime.

Within this long historical process, the Manchu language and the Eight Banner system later developed into important integrative mechanisms that linked military organization, social structure, administration, and everyday life. These institutions did not replace earlier regional cultures but absorbed and reorganized diverse traditions into a new composite order that reflected the multi-ethnic foundation of the region.

Today, Manchuria is understood not only as a historical territory, but as a shared cultural and intellectual concept that transcends modern national boundaries. Research on Manchuria engages questions of language, environment, migration, ethnicity, belief, and memory across China, Russia, Korea, Mongolia, and the wider Northeast Asian world. It stands as a distinctive civilizational zone shaped by long-term coexistence, exchange, and adaptation.

The Society approaches the study of Manchuria from a public cultural and interdisciplinary perspective. We understand “Manchuria” as an inclusive Northeast Asian civilizational space, embracing both Inner and Outer Manchuria and the diverse peoples who have shaped its past and present. Our work seeks to reconnect historical geography with living cultural memory, and to explore how this regional civilization continues to inform contemporary cultural identity and cross-cultural dialogue.

THE EIGHT BANNERS

The Manchu Eight Banner system was instituted between 1601 and 1615 by Nurhaci, ancestor of the Aisin Gioro clan, as the military and social foundation of the Later Jin state. He reorganized the traditional Jurchen tribal structure into eight banners, identified by four paired colors: Plain Yellow, Bordered Yellow, Plain White, Bordered White, Plain Blue, Bordered Blue, Plain Red, and Bordered Red. The system governed not only soldiers but also their families, creating a unified model of military and civil administration.

As the empire expanded, the Eight Banners gradually incorporated Mongols, Xibe, Koreans, and Han Chinese, forming a multi-ethnic military organization that became the core institution of Qing rule. Within the Qing dynasty, bannermen enjoyed higher social status than local Han civilians. As a hereditary elite, they received stipends, land allocations, and official appointments, occupying a central position in the imperial order.

Although the banner system was abolished after the fall of the Qing dynasty, its cultural memory endures. Many descendants of bannermen still identify their ancestral banners when meeting one another, affirming bonds of shared origin. For the descendants of the Aisin Gioro lineage, the banners, family name, and places of origin remain enduring symbols of reverence and connection to their ancestors.

CULTURAL TRADITIONS

The cultural traditions of Manchuria are rooted in the ancient Tungusic civilizations of Northeast Asia and were gradually shaped through centuries of migration, interaction, and regional integration. With the unification of the various Jurchen and related peoples under the leadership of Nurhaci in the early seventeenth century, the name “Manchu” came to represent not only a political identity but also a shared regional civilization formed through the blending of multiple ethnic groups.

Across the vast forests, rivers, and plains of Manchuria, diverse communities—including the Jurchen-Manchu, Hezhe, Oroqen, Evenki, Daur, Xibe, Mongols, Koreans, and Han—developed interwoven ways of life. Despite their diversity, they shared a common ecological environment and many overlapping cultural traditions rooted in the Tungusic world of hunting, fishing, horseback riding, and frontier survival.

Shamanism, one of the oldest spiritual foundations of the region, long served as a core belief system connecting humans, nature, and the spirit world. The color white was traditionally revered as a symbol of purity, auspiciousness, and spiritual power. Falconry, archery, and horsemanship were valued not only as practical skills but also as expressions of social status and cultural refinement. The custom of revering crows—linked to ancestral legends of protection and survival—later developed into the practice of feeding crows within banner communities, becoming a distinctive cultural symbol of the Manchu world.

With the establishment of the Eight Banner system, many of these earlier regional traditions were reorganized into a unified social and military structure. Banner affiliation, clan identity, and shared ritual practices formed a collective framework through which cultural memory was transmitted across generations. Customs associated with hunting, fishing, seasonal migration, food preparation, clothing, and ritual life continued to evolve within this system, creating a living cultural continuity rather than a static tradition.

Over centuries, these shared practices gradually shaped a distinctive Manchurian civilizational identity—one that cannot be reduced to any single ethnic origin, but instead reflects the long-term coexistence and integration of multiple peoples within the Tungusic cultural sphere. Today, these traditions remain an enduring cultural foundation for understanding Manchuria as a living historical region defined by ecological adaptation, spiritual heritage, and multi-ethnic continuity.